7 Semantic Annotation Primer

7.1 Introduction

A semantic annotation creates a relationship between some semantic metadata and a resource - in this case, a dataset, or some other element of a dataset (e.g., an attribute). What makes the annotation “semantic” is that the resource is linked to a well-defined term in a web-accessible ontology. In this way, semantic annotation provides access to precise definitions of concepts, and clarifies the relationships among concepts in a machine-readable way. Creating semantic annotations does require additional effort but pays off by enhancing discovery and reuse of your data.

The main differences between semantic annotation and simply adding keywords are:

- semantic annotations can be read and interpreted by computers

- semantic annotations describe the relationship between a specific part of the metadata and terms in external vocabularies

- semantic annotations use W3C-recommended languages to express these relationships via the Web

For the purposes of this document all mentions of “annotation” imply “semantic annotation” as described above. Generic methods for annotating data and metadata exist (e.g., using keywords), but these are not nearly as powerful as “semantic annotation”.

Benefits of annotation: Annotations enhance data discovery and interpretation thereby making it easier for others to find and reuse data (and thus give proper credit). For example, consider the following cases:

- Finding synonymous concepts: Assume one dataset uses the phrase “carbon dioxide flux” and another dataset “CO2 flux”. An information system can recognize, through semantic annotation, that these datasets are about the same concepts if the datasets were annotated using the same term identifier for that measurement.

- Disambiguating terms: If datasets have been annotated, the system can assist in providing only results relevant for your intended meaning. For example, if you are searching for datasets about “litter” (as in “plant litter”), other irrelevant terms also labelled as “litter” (e.g., “garbage” or a “group of animals born together”) can be eliminated from your search results. This is because each distinct type of “litter” would be associated with a different identifier.

- Hierarchical searches: If you search for datasets containing “carbon flux” measurements, then datasets annotated as having measurements of “carbon dioxide flux” or “CO2 flux” will also be returned because these are both types of “carbon flux”. This is possible if the concepts come from a structured vocabulary where “carbon dioxide flux” is lower in the hierarchy (i.e., is a subclass) of “carbon flux”.

There are five locations within the EML 2.2.0 schema to embed references to terms in external vocabularies (also known as ontologies) using HTTP uniform resource identifiers or URIs. The association of an element in an EML metadata document with that external reference is a semantic annotation. By referencing terms from an external vocabulary, one can provide a rigorous, expressive, and consistent interpretation of the metadata. This is only true, however, if the external vocabulary itself is well-constructed, and expressed in a W3C semantic web language. Since the external reference (or annotation) is to a controlled vocabulary or ontology, the annotation provides a computer-usable pointer (the HTTP URI) that resolves (and dereferences) to a useful description, definition, or specification of other relationships for that annotated resource.

Related FAQ: How do computers use EML annotations?

7.1.1 Take-home messages

- Semantic statements must be logically consistent, as they are not simply a set of loosely structured keywords.

- EML 2.2.0 has five places or methods that accept annotations (described in greater detail below).

- The best place for advice and feedback on EML annotations is your data management community

7.1.2 Organization of this document

The purpose of this primer is to provide an introduction to how semantic annotations are structured in EML documents. It is expected that the readers is already familiar with the EML schema. The central text of the primer (Semantic Annotations in EML 2.2.0) should provide all the information needed to create annotations in EML, with addtional details in a Glossary, list of Vocabularies and repositories used in examples and Frequently asked questions. Longer explanations of some concepts are in the Appendix.

7.1.3 Other Conventions and Terminology

- Use of the terms “required” or “must”: this feature is a requirement of EML 2.2

- Use of the term “should”: this feature is not required by the EML 2.2 schema but is a recommended or emerging best practice. It is not checked by the EML schema or parser, but could be checked or confirmed by an external system.

7.2 Semantic Annotations in EML 2.2.0

There are five locations within the EML 2.2.0 schema where annotations can be included:

- top-level resource: an

annotationelement is a child of thedataset,literature,software, orprotocolelements - entity-level: an

annotationelement is a child of a dataset’s entity (e.g., dataTable) - attribute: an annotation element is a child of a dataset entity’s

attributeelement - eml/annotations: a container for a group of

annotationelements using references - eml/additionalMetadata: annotation elements that reference a main-body element by its

idattribute

7.2.1 Annotation element structure

All annotation nodes are defined as an XML type so they have the same structure anywhere they appear in the EML record. The basic structure is listed below (additional examples are provided in the following sections).

<annotation>

<propertyURI label="property label here">property URI here</propertyURI>

<valueURI label="value label here">value URI here</valueURI>

</annotation>An annotation element always has a parent-EML element, which is the ‘thing’ being annotated, or the subject (e.g., the dataset, attribute). The annotation element has two required child elements: propertyURI and valueURI. Together, these two child elements, along with the subject, form a “semantic statement” that can become a “semantic triple”. The concept of a triple is covered in more detail (see Semantic Triples, below). Here, we concentrate on the structure of an annotation within the EML document itself:

propertyURIandvalueURIelements- each element’s text is the URI for the concept in an external vocabulary. The URI points to a term in a vocabulary where a definition, description, and that term’s relationships to other concepts are formally modelled. Content is required by the EML schema, and it should be a URI.

- the XML attribute

labelis required (for bothpropertyURIandvalueURI)- it should be suitable for application interfaces to display to humans

- it should be populated with values from the referenced vocabulary’s label field (e,g.,

rdfs:labelorskos:prefLabel). Note that this assumes the referenced vocabulary is stored as an RDF document, which is current best practice for sharing scientific vocabularies over the Web.

A note about annotations and element IDs All annotations must have an unambiguous subject. At the dataset-, entity-, or attribute- level, the parent element is the subject (e.g., <dataset>, <dataTable>, <attribute>), and precision of nodes in EML is guaranteed by the element’s id. That is, if an element has an annotation child, it must also have an id so it can become the annotation subject. Annotations at eml/annotations or eml/additionalMetadata will have subjects defined with a references attribute or describes element. As with other internal EML references, an id is required. With EML 2.2.0, the parser will check that an id attribute is present on elements with annotation children. As a reminder, the id must be unique within an EML document. Ideally, that id either is, or can readily be translated into, an HTTP URI that can be dereferenced (see examples below).

7.2.2 Top-level resource, entity-level, and attribute annotations

Annotations for top-level resources, entities, and attributes follow the same general pattern: the subject of the semantic statement is the parent element of the annotation; it must have an id attribute.

7.2.2.1 Example 1: Top-level resource annotation (dataset)

In the following dataset annotation, the semantic statement can be read as “the dataset with the id ‘dataset-01’ is about grassland biome(s)”.

- the subject of the semantic statement is the

datasetelement containing theidattribute value"dataset-01" - the

annotationitself has 2 parts:propertyURIis ‘http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/IAO_0000136’, and describes the nature of the relationship between the subject (above) and object (valueURI below), using a term from the Information Artifact Ontology (IAO).valueURIis ‘http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/ENVO_01000177’, which resolves to the “grassland biome” term in the Environment Ontology (EnvO).

<dataset id="dataset-01">

<title>Soil organic matter responses to nutrient enrichment in the Nutrient Network:Nutrient Network. A cross-site investigation of bottom-up control over herbaceous plant community dynamics and ecosystem function.</title>

<creator id="eric.seabloom">

<individualName>

<givenName>Eric</givenName>

<surName>Seabloom</surName>

</individualName>

</creator>

...

<coverage>

...

</coverage>

<annotation>

<propertyURI label="is about">http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/IAO_0000136</propertyURI>

<valueURI label="grassland biome">http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/ENVO_01000177</valueURI>

</annotation>

...

</dataset> 7.2.2.2 Example 2: Entity-level annotation

In the following entity-level annotation, the semantic statement can be read as “the entity with the id ‘urn:uuid:9f0eb128-aca8-4053-9dda-8e7b2c43a81b’ is about Mammalia”.

- The subject of the semantic statement is the

otherEntitywithidattribute value,"urn:uuid:9f0eb128-aca8-4053-9dda-8e7b2c43a81b". - The annotation itself has 2 parts

propertyURIis “http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/IAO_0000136”, which resolves to “is about”, from IAOvalueURIis “http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/NCBITaxon_40674”, which resolves to “Mammalia” in the NCBI Taxon ontology.

<otherEntity id="urn:uuid:9f0eb128-aca8-4053-9dda-8e7b2c43a81b" scope="document">

<entityName>DBO_MMWatch_SWL2016_MooreGrebmeierVagle.xlsx</entityName>

<entityDescription>Data contained in the file DBO_MMWatch_SWL2016_MooreGrebmeierVagle.xlsx are marine mammal observations and observation conditions from CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier July 10-20, 2016. Data observations and locations are part of the Distributed Biological Observatory (DBO).</entityDescription>

<physical scope="document">

<objectName>DBO_MMWatch_SWL2016_MooreGrebmeierVagle.xlsx</objectName>

<size unit="bytes">24635</size>

</physical>

<entityType>Other</entityType>

<annotation>

<propertyURI label="is about">http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/IAO_0000136</propertyURI>

<valueURI label="Mammalia">http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/NCBITaxon_40674</valueURI>

<annotation>

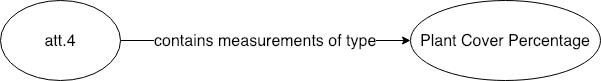

</otherEntity>7.2.2.3 Example 3: Attribute annotation

In the following attribute annotation, the semantic statement can be read as “the attribute with the id ‘att.4’ contains measurements of type plant cover percentage”

- The subject of the semantic statement is the

attributeelement with theidvalue “att.4”. - The annotation itself has 2 parts

propertyURIis “http://ecoinformatics.org/oboe/oboe.1.2/oboe-core.owl#containsMeasurementsOfType”, from the Extensible Ontology for Observations (OBOE)valueURIis “http://purl.dataone.org/odo/ECSO_00001197”, which resolves to “Plant Cover Percentage” in the Ecosystem Ontology (ECSO)

Related FAQ: Are all EML dataTable attributes measurements?

<attribute id="att.4">

<attributeName>pctcov</attributeName>

<attributeLabel>percent cover</attributeLabel>

<attributeDefinition>The percent ground cover on the field</attributeDefinition>

<annotation>

<propertyURI label="contains measurements of type">http://ecoinformatics.org/oboe/oboe.1.2/oboe-core.owl#containsMeasurementsOfType</propertyURI>

<valueURI label="Plant Cover Percentage">http://purl.dataone.org/odo/ECSO_00001197</valueURI>

</annotation>

</attribute>7.2.3 Annotations grouped under the EML <annotations> element

Examples 1-3 above show annotations directly beneath the parent element, which is the semantic subject. However, all the annotations for an entire dataset can be grouped together instead of nested below a parent element. This can be accomplished in two ways/places: (1) in an <annotations> element (example 4), and (2) under <additionalMetadata> (example 5).

When the annotations are grouped together, each annotation must have its subject designated by a references attribute that points to the id attribute of the element being annotated (the subject). That is, what is listed in the references attribute is the id of the subject of the semantic annotation. An implication of this is that that any EML element with an id can become the subject of an annotation.

7.2.3.1 Example 4: Annotating with the <annotations> element

All the annotations for a resource can be grouped together under an annotations element. With this construct, each annotation must have its subject specifically identified with a references attribute that points to the subject’s id. The <annotations> element is a sibling of the top level element (e.g., <dataset>), and appears after it, just before <additionalMetadata>.

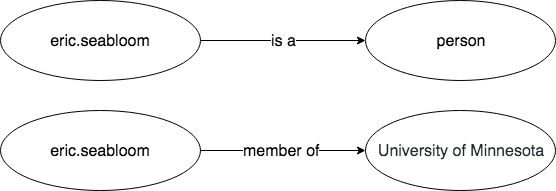

This example contains 3 different annotations:

In the first, the subject is the dataTable element with the id of “CDF-soil-table”. Its annotation components are analogous to Example 2 above, again referencing terms in IAO and ENVO. The semantic statement can be read as

- “the dataTable with the

id‘CDR-soil-table’ is about grassland biome(s)”.

The second and third annotations both have individual persons as their subjects – the creator element that has the id “eric.seabloom”.

Respectively, their semantic statements can be read as

- “‘eric.seabloom’, the creator (of the dataset), is a person”.

- “‘eric.seabloom’, the creator (of the dataset), is a member of University of Minnesota”.

The ontologies used for eric.seabloom are

- in the second annotation

propertyURI: uses an RDF built-in type, rdf:type that has label “is a” (as in,the subject *is an* instance of a class)valueURI: schema.org’s concept of a “person”

- third annotation

propertyURI: another schema.org concept for a relationship, “is a member of”valueURI: the DOI, which is managed by Research Organization Registry, for the organization University of Minnesota.

<eml>

...

<dataset id="dataset-01">

<title>Soil organic matter responses to nutrient enrichment in the Nutrient Network:Nutrient Network. A cross-site investigation of bottom-up control over herbaceous plant community dynamics and ecosystem function.</title>

<creator id="eric.seabloom">

<individualName>

<givenName>Eric</givenName>

<surName>Seabloom</surName>

</individualName>

</creator>

<dataTable id="CDR-soil-table">

<entityName>e247_Soil organic matter responses to nutrient enrichment in the Nutrient Network</entityName>

...

</dataTable>

</dataset>

<annotations>

<annotation references="CDR-soil-table">

<propertyURI label="is about">http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/IAO_0000136</propertyURI>

<valueURI label="grassland biome">http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/ENVO_01000177</valueURI>

</annotation>

<annotation references="eric.seabloom">

<propertyURI label="is a">http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#type</propertyURI>

<valueURI label="Person">https://schema.org/Person</valueURI>

</annotation>

<annotation references="eric.seabloom">

<propertyURI label="member of">https://schema.org/memberOf</propertyURI>

<valueURI label="University of Minnesota">https://ror.org/017zqws13</valueURI>

</annotation>

</annotations>

<additionalMetadata>

...

</additionalMetadata>

</eml>7.2.4 Annotations grouped under <additionalMetadata>

Like the annotations grouped under <annotations>, annotations can also be grouped under <additionalMetadata>. If an additionalMetadata section holds a semantic annotation, it must have a describes element (to hold the subject) with a metadata element containing at least one annotation element.

- The subject of the semantic statement has its id contained in the

describeselement. - The annotation itself is within the

additionalMetadatametadatasection. - Multiple

annotationelements may be embedded in the samemetadataelement to assert multiple semantic statements about the same subject. - To annotate different subjects, it is best to use multiple

additionalMetadatasections, each with a single subject.

7.2.4.1 Example 5: additionalMetadata element annotation

Example 5 shows one of the same annotations as presented in Example 4, but here is contained in an additionalMetadata section.

The semantic statements can be read as “‘eric.seabloom’, the creator (of the dataset), is a person”.

- The subject of the semantic statement is the EML

creatorelement with theidattribute “eric.seabloom”. - The annotation itself has 2 parts

propertyURIis “https://schema.org/memberOf”, which resolves to “is a member of”, from schema.orgvalueURIis “https://ror.org/017zqws13”, a DOI which resolves to “University of Minnesota”.

<eml>

...

<dataset id="dataset-01">

<title>Soil organic matter responses to nutrient enrichment in the Nutrient Network:Nutrient Network. A cross-site investigation of bottom-up control over herbaceous plant community dynamics and ecosystem function.</title>

<creator id="eric.seabloom">

<individualName>

<givenName>Eric</givenName>

<surName>Seabloom</surName>

</individualName>

</creator>

<dataTable id="CDR-soil-table">

<entityName>e247_Soil organic matter responses to nutrient enrichment in the Nutrient Network</entityName>

...

</dataTable>

</dataset>

...

<additionalMetadata>

<describes>eric.seabloom</describes>

<metadata>

<annotation>

<propertyURI label="member of">https://schema.org/memberOf</propertyURI>

<valueURI label="University of Minnesota">https://ror.org/017zqws13</valueURI>

</annotation>

</metadata>

</additionalMetadata>

</eml>7.3 Glossary

dereference: To interpret a uniform resource identifier (URI), and retrieve information about the resource identified by that URI. See resolve.

Internationalized Resource Identifier (IRI): An extension of ASCII characters subset of the Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) protocol.

JSON-LD (JavaScript Object Notation for Linked Data), is a method of mapping from JSON to an RDF model. It is administered by the RDF Working Group and is a World Wide Web Consortium Recommendation.

knowledge graph: Any knowledge base that is represented as a mathematical graph. In the mathematical sense, a graph is simply a collection of points connected by lines. The points are called nodes or vertices, while the lines are called edges or links. In an informatics sense, this structure is used to store information about a set of objects, including the identity of the objects (as nodes), and the relationships among the objects (as links). Note that the use of the word “object” here is very general, and is not the same sense as when we describe triples.

In an RDF (semantic) triple, the subject and object (the word object here in the specific RDF sense!) are represented as nodes, and the relationship between the nodes is represented as an edge or link. Note however that a subject of one triple can serve as an object of another triple, and vice-versa. The term Knowledge Graph is generally used nowadays to refer not so much to an underlying controlled vocabulary or ontology, but rather to the assertions about various objects and how these relate to ontology terms, and other objects. Thus, as a set of semantic annotations grows, for example, assertions (triples) about datasets, these would be stored in a growing knowledge graph. The most famous Knowledge Graph as of today is the one that informs search results for Google.

ontology: In an informatics sense, an ontology is a representation of a corpus of knowledge. The W3C-recommendation is that these representations be constructed using an RDF data model, that has a graph structure. The ontology provides a representation of a set of terms, including their names, and descriptions of the categories, properties, and relationships among those terms.

pointer: A kind of reference to a datum stored in computer memory.

resolve: To interpret a URI and determine a course of action for dereferencing the URI. See dereference .

Resource Description Framework (RDF): A World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) recommendation that enables the encoding, exchange, and reuse of structured metadata using a graph model. The RDF data model employs semantic triples composed of a subject, predicate, and object to share and integrate data across different applications and communities through the Web.

uniform resource identifier (URI): In its most general sense, a URI is simply a string of characters that unambiguously identifies a particular resource. Much more commonly, it refers to an identifier for a resource on the Web, but, e.g. ISBN numbers are also URIs. For semantic annotations, the components of semantic triples are ideally HTTP URIs that dereference using Web technology, to an appropriate representation of a resource, e.g. metadata about the dataset in the case of the subject, and definitions and descriptions of the meaning of the predicate and object terms that provide information about the subject.

7.4 Vocabularies and repositories used in examples

Communities using EML annotations will develop recommendations for suitable vocabularies, based on their own requirements (e.g., domain coverage, structure, adaptability, reliabliity and maintenance model). The following ontologies are already widely used, were employed in the examples above, and are in use by (and in some cases managed by) the authors.

- ECSO (Ecosystem Ontology) (https://github.com/DataONEorg/sem-prov-ontologies/tree/master/observation). An ontology for ecosystem measurements led by NCEAS.

- EnvO (Environment Ontology) (http://www.obofoundry.org/ontology/envo.html) An OBO Foundry ontology for the concise, controlled description of environments.

- IAO (Information Artifact Ontology) (http://www.obofoundry.org/ontology/iao.html) An OBO Foundry ontology of information entities.

- NCBITaxon Ontology http://www.obofoundry.org/ontology/ncbitaxon.html An OBO Foundry ontology representation of the National Center for Biotechnology Information organismal taxonomy.

- OBOE (Extensible Ontology for Observations) (https://github.com/NCEAS/oboe) An ontology for scientific observations and measurements developed by DataONE and NCEAS.

- ROR (Research Organization Registry) (https://ror.org/) A global registry of research organizations.

- schema.org (https://schema.org/) An initiative to create and support common sets of structured data markup on web pages. Extensions work with the core vocabulary to provide more specialized and/or deeper vocabularies.

7.5 Frequently asked questions

Below are answers to questions some readers had, which may be helpful to you. If you have additional questions, please bring them up in your community for feedback.

Q: Why do EML elements with annotations need id attributes?

A: EML elements that have annotation children need id so that they can be used to construct the subject of

an RDF triple. See above.

Q: What is the difference between ‘dereference’ and ‘resolve’?

A: Within the context of semantic annotation, “dereferencing” refers to the process of interpreting a URI, and providing “useful information” back about the Resource of interest. The phrase “resolving a URI” is often used synonymously with “dereferencing”, but technically “resolution” refers to the process of determining HOW and WHAT to do with the URI, whereas “dereferencing” is explicitly about the action taken, which is typically retrieving a representation of the Resource of interest. The formal specification for these terms and what they mean is found in the IETF’s (Internet Engineering Task Force) RFC (Request for Comment) 3986 (https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc3986).

Q: What is the difference between an URI and a URL? Example URIs look a lot like URLs… What about IRIs?

A: The distinctions among URIs (Uniform Resource Identifiers), URLs (Uniform Resource Locators), and URNs (Uniform Resource Names), relate to differentiating the functionalities of identifying a Resource, as opposed to locating a Resource, or doing both. URLs are all URIs (with some edge case exceptions subject to argument), and URNs are also URIs. In many cases, URIs serve both to name and locate a Resource.

Within the vision of the Semantic Web, URIs are ideally unique, persistent URNs identifying some Web Resource, that can also serve to locate and retrieve (dereference) a representation of that Resource (URLs). The formal specification for these terms and what they mean is found in the IETF’s RFC 3986, section 1.1.3 (https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc3986#section-1.1.3). Another acronym one may encounter with increasing frequency is IRI (Internationalized Resource Identifier) that extends the concept of an HTTP URI to allow for use of the full Unicode character set, rather than just ASCII, in its construction (https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc3987).

Q: What is SKOS?

A: SKOS (Simple Knowledge Organization System) is a W3C recommendation for organizing a vocabulary in thesauri, taxonomies, and other classification schemes. SKOS provides a set of concepts and properties, that, when expressed in a formal RDF-compatible syntax, can assist with interpreting the relationship of terms with one another, such as defining some category as broader than another. For example, one could state in SKOS syntax, that “animals” is a broader concept than “mammals”. Definitive specification of SKOS can be found at https://www.w3.org/TR/2009/REC-skos-reference-20090818/. SKOS does not provide strong semantics (see RDFS example below), but SKOS concepts and properties can be used within more expressive knowledge organization frameworks, such as RDFS/OWL ontologies.

Q: What is RDFS?

A: RDFS stands for Resource Description Framework Schema. It extends the formal vocabulary for describing Resources expressed in an RDF data model (i.e., a graph).

“Base RDF” is the set of concepts for creating a graph model of data (triples relating a subject, predicate, and object). RDFS adds to the base RDF model by specifying other well-defined concepts and properties, such as rdfs:Label, rdfs:Class and rdfs:subClassOf. These and other RDFS classes and properties, enable data and knowledge modellers to express many relationships between the Subject and Object of a Triple.

In the context of the Semantic Web, the RDF model relies extensively on dereferenceable URIs in the subject and predicate positions, and URIs or literals in the object position (there are small formal exceptions to this not immediately relevant here). RDF triples can be expressed in several syntaxes, including XML, JSON-LD, and Turtle, among others. RDFS then can be used to enrich the precision and expressivity of the components of a triple, as well as clarify the relationships among these.

- Base RDF: https://www.w3.org/TR/2014/REC-rdf11-concepts-20140225/

- RDFS: https://www.w3.org/TR/rdf-schema/

Q: Are all EML dataTable attributes “measurements”?

A: Yes, in the context of a data table and for annotation purposes, any attribute (observation or column of data) can be considered ‘a measurement’. A philosopher might disagree, saying that some content you might see in data columns (e.g., unique identifiers) are not really measurements; but many other nominals, i.e. text strings identifying some class types (e.g. predator, lizard, tundra), imply quantification and can be construed as measurements.

Q: Can you provide an example of a controlled vocabulary with an rdfs:label or skos:label?

A: Most Semantic Web vocabularies make extensive use of rdfs:label or SKOS label properties. For example, this URI: http://purl.dataone.org/odo/ECSO_00000536 is from the ECSO ontology, under development at NCEAS by NSF’s DataONE and Arctic Data Center. Within that ontology, the URI is associated with an rdfs:label of “Carbon Dioxide Flux”, and a skos:altLabel of “CO2 flux”. If you dereference the URI, you will see how the BioPortal ontology repository displays this information– providing a human-readable representation of the underlying RDF/OWL language in which the ontology is stored.

Q: How do computer use EML annotations?

A: Annotations can be extracted from the EML document, and re-expressed (formally, “serialized”) into a Semantic Web language such as RDF or JSON-LD. Annotations (also called “assertions” or “triples” in RDF) collectively contribute to a knowledge graph, that captures understanding of the relationship of the contents of datasets (as “instances”) with the concepts represented by terms in ontologies (as “classes”).

Q: An image of an RDF graph is great, but a computer doesn’t parse that. What does the RDF look like?

A: Actual RDF (XML) is shown in the code blocks of Example 3 and Example 4.

RDF is a data model based on triples, each of which has three components: a subject, predicate, and object, that are constructed of dereferenceable URIs. RDF triples can be “serialized” in several syntaxes, including XML, JSON-LD, Turtle, N-Triples, and others. These syntaxes are isomorphic, such that translations of RDF graphs from one serialization to another are available– enabling consistent interpretation by machines.

For human interpretation the most straightforward serialization of RDF graphs is N-Triples, where an RDF triple could look like this:

http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/CHEBI_16526 http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/RO_0000087 http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/CHEBI_76413 .

These are three URIs here– representing the Subject, Predicate, and Object of a Triple. The “.” indicates the end of the Triple. Of course, you would need to know that these three URI’s are intended to be interpreted as an RDF Triple. Dereferencing these URIs (e.g. a Web browser or specialized application) one can see that this Triple represents the statement:

“Carbon dioxide”(Subject) “has role”(Predicate) “Greenhouse Gas”(Object)

While the phrasing is a bit awkward sounding, the meaning is clear by simply depicting the rdfs:labels of those terms from the ChEBI (Chemical Entities of Biological Interest) and RO (Relation) ontologies, that are both robust OBO Foundry ontologies.

As another example: http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/NCIT_C20461 http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/creator https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1279-3709 .

that asserts:

“World Wide Web”(Subject) “creator”(Predicate) “Timothy Berners Lee”(Object) .

…although some semantic purists might question whether the Dublin Core property “Creator” can be used in this way as an RDF predicate, since it is not semantically defined– would its rdfs:label be “creatorOf” or “hasCreator”? (Dublin Core does not say explicitly, but implicitly is indicative of “hasCreator”!). Regardless of the formal semantic well-formedness of this Triple, however, one can see the expressive power of the RDF data model, and the value of dereferenceable URIs.

A better solution would be to use the semantically defined term from SIO (the Semantic Science Integrated Ontology) http://semanticscience.org/resource/SIO_000364 as the predicate, with an rdfs:label “has creator”

http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/NCIT_C20461 http://semanticscience.org/resource/SIO_000364 https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1279-3709 .

…that would translate as (based on content of the rdfs:label):

World Wide Web(Subject) has creator(Predicate) Tim Berners-Lee(Object)

or inversely, one could use http://semanticscience.org/resource/SIO_000365 as the predicate, that has rdfs:label “is creator of”

Tim Berners-Lee(Subject) is creator of(Predicate) World Wide Web(Object)

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1279-3709 http://semanticscience.org/resource/SIO_000365 http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/NCIT_C20461.

Within the SIO ontology, SIO_000364 and SIO_000365 are defined as inverses of one another. This enables one (a person or a computer!) to ask either question– “who created the Web?” (A: Tim Berners-Lee), or “what did Tim Berners-Lee create” (A: the Web)– even though you only asserted one of the Triples.

Finally, it is worth noting that one’s choice of which Ontologies to use is important. Within the Ecological and Environmental sciences, there are several highly-recommended vocabularies, including those from the OBO Foundry (e.g. ChEBI, EnvO, RO, and PATO), as well as SIO. Specifically for annotating scientific measurements, NCEAS is developing an Ontology for Ecosystem Measurements, ECSO (with the Arctic Data Center and DataONE). These use, where possible, terms from the OBO Foundry ontologies mentioned here. We have used all these in the examples.

Q: Are there tools available to help data managers select subjects, predicates, and objects to annotate with?

A: Yes, tools are being built to assist with the semantic annotation of EML documents. In addition, tools are being built to enable semantic search, that use the annotations to expand searches to capture synonyms, differentiate homonyms, and enable the discovery of sub-classes of the terms that you might originally be searching for.

7.6 Appendix

7.6.1 Semantic triples

Semantic annotations enable the creation of what are called triples, that are 3-part statements conforming to the W3C recommended RDF data model (learn more: https://www.w3.org/TR/rdf11-primer/). The newly introduced Semantic Annotation capabilities introduced in EML 2.2.0 are constructed in a way that affords relatively straightforward re-expression of those annotations as true RDF triples.

A triple is composed of three parts: a subject, a predicate (that can be an object property or datatype property), and an object.

[subject] [predicate] [object]These components are analogous to parts of a sentence: the subject and object can be thought of as nouns in the sentence and the predicate (object property or datatype property) is akin to a verb or relationship that connects the subject and object. The semantic triple expresses a statement about the associated resource, that is the subject.

There are (perhaps unfortunately) several other ways that the components of an RDF statement are sometimes described. One popular “synonymy” for subject-predicate-object is resource-property-value, i.e. the subject is referred to as the resource, the predicate a property, and the object a value. This can be confusing, since the usual definition of a resource in the context of the World Wide Web is any identifiable ‘thing’ or object, especially one assigned a URI; and by this definition, resources can and often do occur in all three components of a triple. But thinking of a triple as a resource-property-value does provide an indication of the directionality of the semantics of an RDF statement. This latter terminology is also similar to how analogous components are named in JSON-LD. Note that JSON-LD is closely compatible with RDF, and one format can often be readily translated to the other (although there are some exceptions).

Semantic annotations added to an EML document can be extracted and processed into a semantic web format, such as RDF/XML. These “semantic” statements, i.e. RDF triples, are interpretable by any machines that can process the W3C standard of RDF. Those RDF statements collectively constitute the Semantic Web.

7.6.2 URIs

Ideally, the components of the semantic triple should be globally unique and persistent (unchanging), and consist of resolvable/dereferenceable HTTP uniform resource identifiers (URIs; or more formally, IRIs). The subjects of most EML semantic annotations will likely be HTTP URIs that identify the dataset resource itself, or specific attributes or other features within a dataset. The objects of EML semantic annotations, as well as the predicates that relate the subject to the object, will most typically be HTTP URI references to terms in controlled vocabularies (also called “ontologies”) accessible through the Web, so that users (or computers) can dereference the URIs and look up precise definitions and relationships of these resources to other terms.

An example of a URI pointing to a term in a controlled vocabulary is: http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/ENVO_00000097.

When entered into the address bar of a web browser, the abpve URI resolves to the term with a label of “desert area” in the Environment Ontology (EnvO). Users can learn what this URI indicates and explore how the term is related to other terms in the ontology simply by dereferencing its URI in a web browser. All those other aspects you see on the Web page describing “http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/ENVO_00000097” are from other RDF statements (triples) related to “ENVO_00000097”, and that have been rendered into HTML. From here, you might decide that “http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/ENV0_00000172” (“sandy desert”) is a better annotation for your object.

An RDF triple can be constructed as follows, with subject URI, predicate URI, and object URI:

<<https://doi.org/10.6073/pasta/06db7b16fe62bcce4c43fd9ddbe43575>> <<http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/RO_0001025>> <<http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/ENVO_00000097>>.

… indicating that the referenced dataset (subject/resource) was “located in” (predicate/property) a “desert area” (object/value). Note that when expressing a semantic triple, a blank-space must separate the subject, from the predicate, from the object, and that a “period” completes the triple. This is a valid RDF triple, expressed in N-Triple syntax. RDF is most often serialized into XML, however, as Web browsers and many applications are good at parsing XML.

While our focus here is on the semantic annotation of EML documents, it is easy to see how the RDF statements can be used to describe and inter-relate any resources that have unique, persistent HTTP URIs!

Note that the above RDF triple consists of three HTTP URIs. While the exact distinction among what is a URI, a URN, and a URL can be debated, for our purposes, these HTTP URIs can be considered both the name and web location of a resource. Content negotiation between a Web server and a client (which might be a browser, or a Python or R script) can enable an HTTP URI to dereference in ways optimized for the requesting client – e.g. in one case, presenting a human-readable view of metadata for a dataset, and in another, activating a download of that dataset for import into a script.

Semantic annotations in EML are useful because they enable associating data objects described in EML, with terms from external vocabularies. These external vocabularies can be used by other systems to similarly describe data objects, dataset variables, etc. The ability to extract semantic annotations out of EML, and convert these into valid RDF triples, provides further utility that is a pathway to the future. Sets of RDF triples, called “graphs”, or in this case more accurately, “knowledge graphs” (since these triples describe our understanding of data set contents and their relationships) is under development at DataONE, NCEAS, EDI, through the rOpenSci project, and elsewhere. The RDF triple described above hopefully gives an idea of how such triples, constructed of dereferenceable HTTP URIs, can be very useful.

Related FAQ: What is the difference between an URI and a URL?

7.6.3 RDF Graphs

In a data-modeling sense, a graph consists of resources linked to other resources. Thus, the simplest graph structure is a triple, that consists of two nodes that are somehow linked. This is the basic model underlying RDF: a predicate linking a subject to an object. A graph consists of many triples that can be linked with one another.

Below are examples of how annotations can be converted to RDF triples in RDF/XML, so that the RDF information is now computer-readable. Be aware that there are several formats for serializing RDF, including RDF/XML, Turtle, N-Triples, and N3, that vary in the level of how human-readable they are– although these are all machine-readable with complete consistency.

The process of converting (i.e., extracting) a semantic annotation in EML into RDF, is done by parsing applications under development at EDI, NCEAS, rOpenSci, and other data repositories. Careful examination of the examples below also show references to “owl:Class”, “owl:ObjectProperty”, and other statements that may not be familiar. These are fundamental entities or building blocks in W3C-recommended Semantic Web languages, and are determined by the relationships that the triple component identifiers (HTTP URIs) have within their native knowledge graph/ontology.

Related FAQ: What is RDFS?

Related FAQ: An image of an RDF Graph is great, but a computer doesn’t parse that. What does the RDF look like?

7.6.3.1 Graph from Example 3 XML, using attribute/annotation :

RDF example A

<rdf:RDF

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:owl="http://www.w3.org/2002/07/owl#">

<rdf:Description rdf:about="att.4">

<owl:ObjectProperty rdf:about="http://ecoinformatics.org/oboe/oboe.1.2/oboe-core.owl#containsMeasurementsOfType">

<owl:Class rdf:about="http://purl.dataone.org/odo/ECSO_00001197" />

</owl:ObjectProperty>

</rdf>

</rdf:RDF>7.6.3.2 Graph from Example 4 XML, using annotations element:

RDF example B

<rdf:RDF

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:owl="http://www.w3.org/2002/07/owl#">

<rdf:Description rdf:about="eric.seabloom">

<owl:ObjectProperty rdf:about="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#type">

<owl:Class rdf:about="https://schema.org/Person" />

</owl:ObjectProperty>

<owl:ObjectProperty rdf:about="https://schema.org/memberOf">

<owl:Class rdf:about="https://ror.org/017zqws13" />

</owl:ObjectProperty>

</rdf>

</rdf:RDF>7.6.4 Check for Logical Consistency

With semantic annotation, you are adding precise definitions of concepts and relationships that can be traversed with computer logic. Annotations are not simply a set of loosely structured keywords! This is a really powerful addition to EML, and so it comes with some risk. The main thing you should ensure is that your annotations are logically consistent.

The simplest way to check your logic is to write out the RDF triple components and see if it makes sense as a sentence.

[subject (element-id)] [predicate (propertyURI)] [object (valueURI)]

[att.4] [contains measurements of type] [plant cover percentage]

The graph examples (Example 3 RDF graph, Example 4 RDF graph) make ‘true’ statements that are logically consistent:

- att.4 contains measurements of the type plant cover percentage

- eric.seabloom is a person

- eric.seabloom, member of University of Minnesota

However, below is the kind of statement you would NOT want to make:

[eric.seabloom] [is a type of] [measurement]If you suspect your RDF triple might look like this, you should go back and examine the way you structured the annotation.

Things to check:

- Be sure you have used the right classes, properties, or vocabularies for your annotation components

- Become familiar with the vocabularies in your annotation, especially any labels, definitions, and relationships associated with your term(s) of interest.

- Check with your community for specific recommendations on the best vocabularies to use for annotations at different levels. Our examples use well-constructed vocabularies.

- In

additionalMetadata, don’t combineannotationswith more than onedescribeselement. EML allows 1:manydescribeselements in a singleadditionalMetadatasection. So if you have 2describesand 2annotations, you will have 4 RDF statements. Make sure they are all true, and if not, break them up into multipleadditionalMetadatasections.

7.6.5 Additional background information

Following are tutorials and supplemental background reading

LinkedDataTools tutorial: http://www.linkeddatatools.com/introducing-rdf

RDF data model: https://www.w3.org/TR/WD-rdf-syntax-971002/

W3C RDF primer: https://www.w3.org/TR/rdf11-primer/

A tidyverse lover’s intro to RDF https://ropensci.github.io/rdflib/articles/rdf_intro.html

Tim Berners-Lee’s article on the semantic web:

Berners-Lee, T., Hendler, J., & Lassila, O. (2001). The semantic web. Scientific american, 284(5), 34-43.